The Internet's Original Sin

Shoshana Wodinsky explains bad ads.

Welcome to Galaxy Brain — a newsletter from Charlie Warzel about technology and culture. You can read what this is all about here. If you like what you see, consider forwarding it to a friend or two. You can also click the button below to subscribe. And if you’ve been reading, consider going to the paid version.

Reminder: Galaxy Brain has audio versions of the posts for you to enjoy. I’ve partnered with the audio company, Curio, to have all newsletters available in audio form — and they are free for paid subscribers.

This is the longest Q&A I’ve ever done here on Galaxy Brain. There’s quite a bit, here. But I think it’s worth the read. Let me explain why. My first reporting job was at the advertising trade magazine, Adweek. When I started, the ad industry was just beginning a wild, digital transformation. This thing called programmatic advertising was taking off. Ads were sold on these exchanges in these split-second auctions and it felt like dozens of companies were springing up every second. I didn’t fully understand it, but it seemed not all that nefarious at the time.

But the more I started reporting on digital privacy issues, the more it became extremely clear that this huge, opaque online advertising ecosystem was a lucrative blackbox, powered by our personal data. It grew faster than anyone could regulate it, so it was barely regulated. It was (is) ripe with billions of dollars of fraud per year ($52 billion in 2020). And because the system is so hard to understand, it’s ripe for bad actors to use it to pollute the internet with garbage ads. The online ad ecosystem is helping to fund most every publication — including those that spew hate or misinformation. The online ads game is at the center of Google and Facebook’s dominance, too. Most everything bad about the internet (and a lot of good things too) has at least a little bit to do with this ecosystem.

What you’ll realize the moment you start reporting on this world is that it is convoluted and extremely difficult/technical to parse. To do a decent job, you have to immerse yourself in the weeds. Shoshana Wodinksy (a former Adweek alum, too) over at Gizmodo is arguably the reporter that is deepest in the weeds on this subject. Wodinksy isn’t afraid to comb through pages of marketing pitch decks and obscure developer reports or an apps code. And it shows. Her explainers help me understand what’s actually going on in the bowels of the internet and where the money comes from. I caught up with her last week to talk about online advertising, which I sometimes think of as the internet’s original sin.

Hello. Let’s talk about adtech. How’d you get started on this beat?

So, yeah, I never really planned to write about adtech.

How’d you get sucked into it?

I graduated journalism school at the end of 2018 and I really wanted to write about tech stuff. The folks at Adweek reached out and said, ‘this will sound crazy but we’re hiring for an adtech reporter and think you’d be good.’ I didn’t know hardly anything about adtech. My soon-to-be editor was interviewing me and explained adtech via how it related to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which was really fresh in everyone’s mind. He was basically like, ‘you know, there are thousands of companies doing very similar things as Cambridge and getting away with it and getting away with a lot of other stunning stuff, too.’

Trade publications are such a great education.

At the trades you start learning the basics, especially the grammar and industry vocabulary. And this adtech shit was mind-numbing. So I spent hours late at night, just reading and pouring over developer documents from unknown ad exchanges. I got extremely lucky because I started out working with Adweek’s other adtech reporter, who was based in the UK and he was so jaded the way great, grizzled journalists are. He was like, ‘never take these companies at their word.’

I started poking around with this in mind and a lot of the company promises fell apart really quickly. What better way to hold power to account than to write about ad fraud and focusing on this mind-numbing weeds-y tech stuff. When it came to small, but meaningful privacy issues, I ended up learning about a a ton of stuff the ad platforms didn’t tell the public. Trade audiences already knew that this stuff was happening but the broader audience didn’t.

This really tracks with what I’ve found over the last decade of learning how to report. I think it’s this way on most beats but I find it especially true in covering privacy and data issues. A lot of this stuff is like, purposefully dense and dull. And the most interesting stuff is always the most impenetrable shit. You basically need almost like an advanced degree to understand how your data moves across the internet.

This is what strikes me about your work. This one piece you wrote in 2020 -- How Google Ruined the Internet (According to Texas) -- has a catchy title but is ultimately an incredibly detailed explainer on the mundane workings of the online ad industry. You start with a primer on how ad servers and exchanges work (basically: detailed automated auctions that happen in less than a second that are fueled by the data companies collect on you based off your browsing history and other collection methods) and move into the way that Google’s dominance in the ad industry forced all kinds of scummy things to happen, including some colluding with Facebook.

Ultimately, you show how wildly boring tech stuff like “header bidding” leads to this race to the bottom that hurts competitors first, then advertisers, then anyone who publishes things online. And the internet turns to this kind of garbage-y, pop-up-y, clickbait-y surveillance hellscape. I guess what I’m saying is that, if you don’t understand the exchange minutiae, you’re not going to really know why the internet is decaying under the weight of these companies.

Back in January there was this controversy over WhatsApp’s privacy policy. Just a ton of confusion and it was clear that both all the people freaking out over the change as well as Facebook’s comms department didn’t really know what they were talking about. For my part, I’d long been familiar with the quirky parts of WhatsApp’s privacy policy and its business model and so I wrote a 2,547 word explainer on it. I screenshotted some of the code that shows what the data collection looks like. It allowed me to show readers that, while the policy update sounded awful, it was essentially just Facebook/WhatsApp saying what they’ve always been doing out loud.

And that, to me, was a good example of demonstrating that, hey, this is a company that exists to make money and ultimately any data collection happening on you is going to happen for profit. So let's talk about who's making money here and where that money is going because if you understand that, then you'll understand how we can fix these things for the better in the future. As you can see, I’m very fun at parties.

Do you think that a lot of the adtech stuff is actually complex because it needs to be? Or do you feel like it's complex because it's the wild west and people are making it up as they go?

I feel like some of the technique is hiding the incriminating stuff in the boring stuff. I think the field is incomprehensible on purpose for two reasons. The first is that, when you talk to people who work in adtech candidly, almost all of them know that the field is rampant with fraud and abuse and really just grifters. I don’t think it would be as complex if it weren’t trying to hide a lot of that fraud. Second, many of these ad companies and data exchanges know investors, shareholders, and hedge funds (which use a lot of this data as corporate intelligence) don’t understand this stuff either. All our personal data is ricocheting back and forth in a giant Russian nesting doll of black boxes and algorithms and nobody is cracking it open because who has the time?

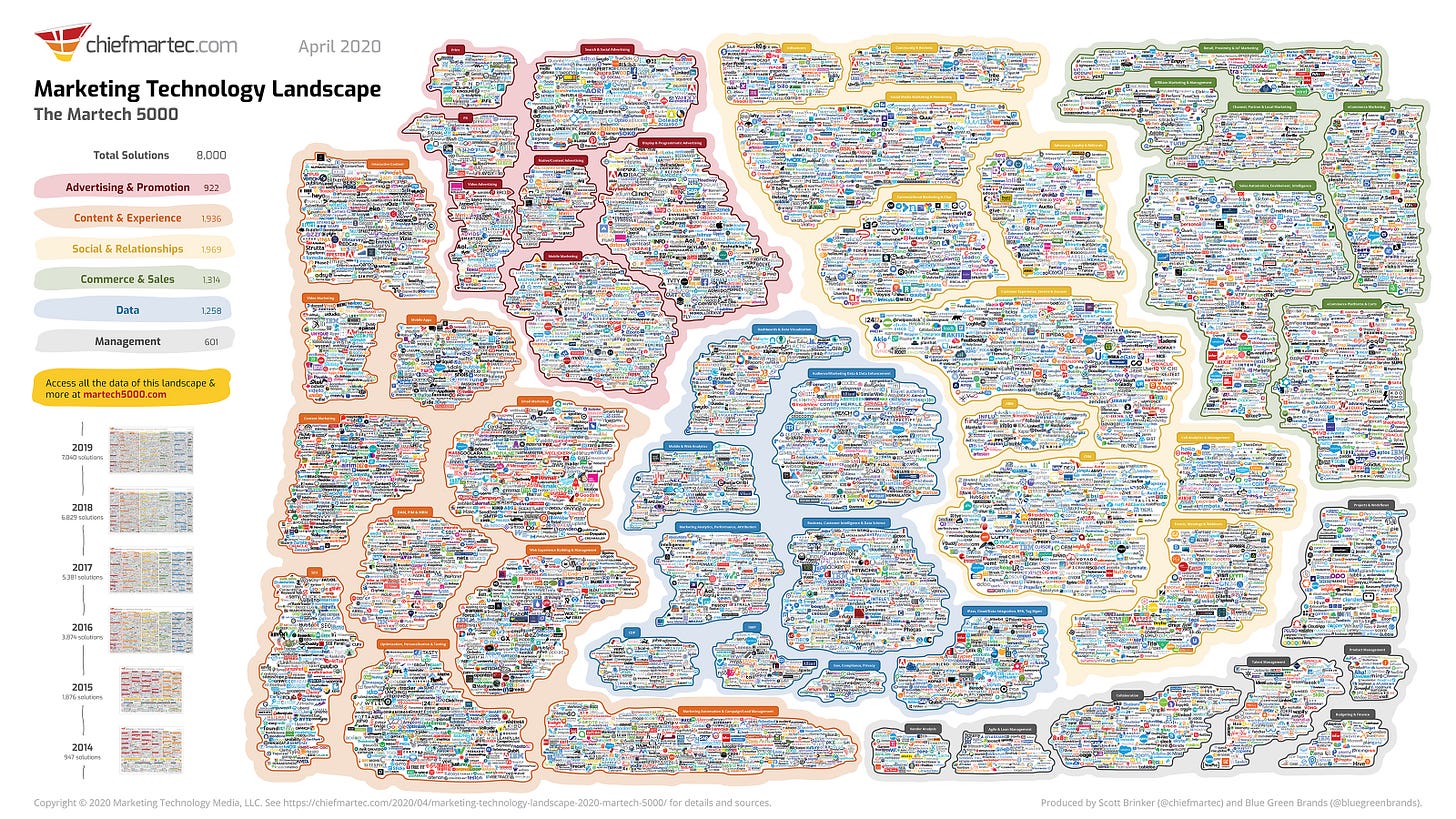

The thing that radicalized me to the adtech mess is the Martech 5000 chart. It shows all the different vendors in the online advertising ecosystem — each tiny logo is a company. I feel like, the moment you look at that chart, it all becomes clear. It’s like, ‘oh, this is very messed up. We have no chance of knowing what’s happening to our data.’ Do you think non tech people have a more sophisticated understanding or even a slight awareness of that system than they did before?

The Martech 5000 is wild. It’s more or less 8000 companies all generating, like, billions of dollars in revenue. When you look at that thing, you're looking at the guts of the internet. Like, that's how the internet gets funded. That's how people like me — I mean almost all media — get our salaries paid. As a journalist, it’s odd because ultimately, if you start talking about what's wrong with digital advertising, you start, you risk fighting the economic engine of your industry. If you write about privacy and targeted ads in particular. You're going to end up with a chorus of dudes online, saying like, ‘you know your website runs targeted ads. Hypocrisy!’

But that’s not really the point. You can critique an oppressive, broken system while also being forced to live within it. If I had a choice, we we wouldn't have targeted ads everywhere but that's not how the digital economy works. And this is an economy that we're talking about. It's just vastly unregulated and all of the transactions and exchanges are happening billions of times per second because of computers.

I think people do care about this ad privacy stuff but they care about it using different language. They don’t talk about this in terms of ‘demand side or supply side ad platforms. They don’t really know about any of these players in, say, the Martech 5000. But people understand when something feels wrong to them. People understand, ‘hey, this company is using my data without my explicit permission. I don't want them to do that.’ Many fundamentally understand that this is how the internet works but they don't have the words to describe how it works.

And the only people who do have the words to explain how it works are deliberately hiding it or they're like Google or Facebook who write privacy policies using words everyone can understand, but in ways that obfuscate what is actually happening there. For example, I combed through Facebook’s privacy policies back in February and it was clear that their very simplistic language is technically, legally correct but doesn’t actually offer any clarity to where your data is going.

That reminds me of a story from my reporting in like 2013. I interviewed a person who used to craft tech company privacy policies and he confessed he thought all the time about how privacy policies are an unfair fight. At that moment where you’re clicking ‘I Accept’ on the policy, he told me that he imagines a big boardroom. On one side of the long table it’s you, just a regular human with little legal expertise. On the other side of the table is a team of 30 highly paid Ivy League lawyers. Just a powerful set of people with one goal: to cover an institution’s ass. It’s that versus a vaguely disinterested person who’s like, ‘I just want this app to load now.’ That image has always stayed with me.

I think it's also indicative of like the way these companies see us. They don't see us as being sophisticated. It’s a problem of scale. These companies are so big, with so many users, they legitimately can’t think in terms of a single user. And so these companies start to see people less like humans with agency and more like of caricatures in these different, generalized buckets. I think this mindset helps explain their process of getting people to give up their data. They ultimately don't care about your personal sense of right and wrong or what feels okay to you and what doesn't feel okay. They’re not thinking about your agency. They want to be profitable because they're a company and that's their job. And, at the end of the day, you might feel upset over what they've done but hey, you’re just one user. You’re not really part of that calculus.

It's a scale issue. We've taught companies that they can grow to basically an infinite scale and thanks to all these connected devices that we're using, they can collect infinite amount of data and build out new forms of data. And if they can monetize literally anything, they’re going to try.

For the Times’ Privacy Project I talked to so many political data people and one thing I kept hearing was that companies are collecting information without really knowing what the utility is. That’s because they are sometimes collecting it and selling it to people — in some instances political campaigns — and functionally lying about what its potential is. And the reason they're doing it is because like the political establishment and like the people who write checks, just still happen to be like Boomers who don't fully understand how smartphones and data colletion work. So you get this cycle where people are collecting information that they either know is worthless or they don't have any idea if it has any value but maybe it will someday. It seems like yet another example of this scale obsession that creates a ‘collect first, figure out efficacy later’ model.

Back at Adweek, I was looking into a story about Palantir and I found out they were easily able to sell their insights tech to the federal government using flashy campaigns and sales pitches. But they couldn’t really sell themselves to marketers. Palantir ultimately just aggregates data and the marketers I talked with said that what Palantir was offering wasn’t that great and was way too expensive. Plus, the marketing industry professionals already knew how to get very cheap location data an other datasets on the market.

What that told me was that people in the federal government and military were able to pay insane amounts of money for data they knew little about. And they’re okay with doing this because they know nobody is going to check.

This brings up something contradictory that I struggle with. A lot of this personal data is cheap to buy. A lot of it is bad, too — corrupted or out of date or not all the reliable. And people in the industry know this. But many people don’t. I think this is like the fundamental brain scrambler of reporting on all this stuff. The invasions of privacy are real. The potential for abuse is real. But also it’s true that there’s a lot of garbage data, the importance of which is being way oversold by marketers and touted by targeting companies. How do you balance those two things in your reporting?

At the end of the day the ethos I try to carry in all my stories is that we all live under capitalism and the only way we do that is by making a profit for somebody at the end of the line. I’m kind of obsessed with charting that line. I do my best to show the flows of information. When you show the third parties that Facebook shares data with, you’re showing the flow of money. But that’s not enough because, as you said, the value of data isn’t always clear.

Mark Zuckerberg is one of the most wealthy people on the planet and so his company must be doing something valuable, right? Facebook is mostly selling ads and making money so people think, ‘my data must be very valuable.’ But the work is trying to add nuance to that story. Yes, your data is very valuable, but only in aggregate. It’s all very sticky and hard to parse out. Your individual data, in the grand scheme, might not be worth a ton on a market but some of that data is very valuable to you. And that means something. For example, health data feels personal and because of that it shouldn’t be commoditized. The stakes are too high. But then then you look at the big picture and your piece of health data is worth a fraction of a cent. Which is also why companies have to collect so much of it, to scale it up.

Can you give me some more examples of this kind of nuance?

A good example of this is that recent story of the priest who was outed because of leaked location data. When that happened, instead of the ‘abuse of privacy’ angle I chose to focus on the reason this data existed in the first place. Take an app like Grindr. Clearly, it’s great that an app like this exists. But no apps are free. They turn a profit collecting data. But it might not be quite as nefarious as it sounds. See, there are certain classes of data that are taboo to target, including data on peoples’ sexuality. But Grindr had a lucrative opportunity to say, ‘Hey if you want to target gay men, you don’t need to plug individually identified gay men into that targeting platform. Instead, you can just plug in the larger dataset of ‘people who use Grindr.’ It’s a way for people to take this sensitive information and use it in a semi anonymous or aggregated set.

You see this same practice happening at scale with health apps, period trackers, you name it. They’ll say, they have a captive audience of pregnant women and if you use our data, you get access to these audiences that are hard to get ahold of. Now, maybe this works and stays safe. But in the priest example, somewhere down the line one of these companies getting this aggregate data leaked it. What I’m trying to say is that what’s happening here is only happening because we created a digital economy where every single thing about us is monetizable and everyone wants to be next billionaire by selling ads or targeting them somehow. It’s a bad incentive structure.

Sometimes it feels so hard to effectively criticize these big technology ecosystems. Because, yes, the problem is so big. It’s this unchecked, accelerated, advanced capitalism and that’s obviously the bigger issue. But the tree is so big and the roots are almost incomprehensibly thick and embedded through the earth that really, you’re stuck hacking away at some smaller branches. But I really like your idea of focusing on nuances. I think they’re so important and sometimes get lost in the (justified) techlash.

I talk about Faecbook a lot and they’re the easy bad guy when it comes to privacy stuff. For good reason! But one thing they do very well is they constantly remind lawmakers that small businesses depend on them for targeted ads. It is absolutely, true. Many small businesses would probably have a very difficult time surviving in 2021 without dumb Facebook ads. And so we’re left with this problem where, when we try to dismantle the Facebook targeted ads machine to make it a more privacy centric thing, small businesses could suffer. It’s a cold, hard fact.

I’ve been called out by other reporters and people in the privacy space for saying what we might do, by making these platforms more privacy centric, is create some blowback for, like, mom and pop shops and other businesses. I’m not saying there’s some great answer here. But it’s important to realize that ads are a foundation of the online ecosystem — for the media, for online commerce. A big reason we transact digitally is because of that foundation. You want to, as you put it, uproot the tree. But also a lot of good people would be S.O.L. if that happened.

I struggle with this! And I think the Facebook/small business thing is a fascinating example. Yes, if you want to tear this part of the thing down you have to be willing to deal with collateral damage because this online, ad-powered ecosystem is very intertwined in everything we do. The ‘Facebook Is Bad’ story is both true but also a potentially limited way to criticize and to force reform in this system.

But I’m not all that sure what the next step is, here. What does reporting and criticism that works toward a better internet look like? Is it just simply like magnifying, small/medium abuses for the rest of time and just hoping that it slowly chips away at the destabilizing and extractive and inequitable parts of these systems? Or are there more effective ways to address and criticize the interconnected nature of the internet?

I think a start is to try to ask and answer and continue to define the question: what does digital privacy mean to people? We hear the word privacy all the time. We all have different understandings of what that word means and companies in their privacy policies define privacy and the use of our data in specific terms that might not be aligned with what we feel is right and wrong and what makes us feel comfortable.

But, again, it’s nuanced. Here’s an example from my life. I got into an argument with some people in the ad industry. I was invited to talk to them about why privacy matters. I used to use this prescription health app as an example. It’s a legit app that gives discounts on drugs. Before I got my first job, I used it so I could be able to afford the prescriptions I need. Naturally, I started looking into the app and found it was sharing the names of my prescriptions with third parties. I brought up that example to the ad guys and I tried to appeal to their humanity.

I said, ‘when I downloaded this app I was a good citizen and read terms of service and privacy policy and I saw this term ‘third parties’ and that some data would be shared in aggregate form. But reading that line and then seeing my specific prescription data hoovered off my phone felt different. I didn’t consent to that when I consented to the privacy policy.’ And the guy said, ‘from a legal standpoint, you did.’ I countered with, ‘sometimes people don’t have a choice when they download an app or piece of tech.’ In my case, the drugs from this app were anti-depressants. If I couldn’t afford them, I would not have been functional. See, I knew I was making a deal with the devil using the app but it would’ve been helpful if they said explicitly which devil it was.

Right, it’s about having some control back.

I try to frame this work in terms of agency and respect. And I think it’s helpful because these companies ultimately don’t have respect for the users. If companies respected us, they wouldn’t hide this stuff. They wouldn’t need to cover their asses like they do.

A customer who downloads an app because they have to is agreeing to some forms of tracking and data collection. But the real problem is that often these companies aren’t giving people a chance. When these companies don’t give us chance, they are taking away our agency. We can care about privacy and care about data but I think a good way to frame these issues from a reporting perspective is talking about choice. Too often we get high falllutin’ and talk about the American Ideal Of Privacy but I don’t know if that helps. It’s talking about choices. Maybe I like targeting ads and want them! Maybe I hate them.

Not everyone wants the same thing, but everyone wants a choice.

If you’re able to go into the code of an app and show people exactly how these companies and technologies take that ability to choose away from you, that is empowering for readers and regulators.

I like framing it in ‘choices,’ especially because, as you note, everyone has a different preference. It’s a great way not to talk down to people or to oversell the privacy invasions from some of these companies as a kind of mind control.

When targeted ads work, some people really like it. I mean that is why the industry exists. That’s why they’re banking on it and spending all this money and effort collecting data at scale. And when it works, we buy shit we don’t need. It’s effective for what it is supposed to do. The problem is figuring out how to do it ethically and in a way that gives us more agency. But fundamentally this stuff will keep happening because it keeps commerce and the economy going and [guttural noise]…

…I’m going to keep that exasperated groan in there, just so you know.

It’s true. The reason advertising exists is to sell shit. A lot of it is shit we don’t need. If they get you to click on an Instagram ad, then it’s all worth it. And if you do click, you’re giving them something that helps fuel the whole game. They’re not paying attention to the ads you don’t see, they’re paying attention to the shirt you bought.

We need to keep having a conversation about what information should be allowed to be monetizable and what shouldn’t be. We need to have that conversation. That is something I think about every goddamn day. Because from my research and spending infinite hours over the last two years and from reading enough code and pitch decks, I know these guys won’t be satisfied till they’re able to market to you every second of every day of every year.

You said early on that, despite the beat, you’re optimistic about the world you cover. Why?

I do think there is a growing understanding in this field. Take the Cambridge Analytica reporting. You can argue with the sensationalizing of parts of it but it also made people realize something was wrong. It put Facebook’s feet to the fire. And sure, some people might get carried away and come away with batshit ideas about how the advertising industry works and that it’s mind control. But in the long run it makes people care. Then, they speak up. If enough do, then lawmakers listen. Then things change...slowly. These companies doing everything to obfuscate. It’s a game of cat and mouse but it’s the job of us reporters to remind people they have a choice.

Ok! That’s it for today. If you read this newsletter and value it, consider going to the paid version, and come hang out with us on Sidechannel, the Discord you’ll get access to if you switch over to paid.

If you are a contingent worker or un- or under-employed, just email and I’ll give you a free subscription, no questions asked. If you’d like to underwrite one of those subscriptions, you can donate one here.

If you’re reading this in your inbox, you can find a shareable version online here. You can follow me on Twitter here, and Instagram here. Feel free to comment below — and you can always reach me at charliewarzel@gmail.com.

5 steps to fix social media and online advertising through legislation

1. Companies must a publish a technical specification of all information they collect and store about people that use their service, from the perspective of an individual person using their service. This specification must include which of that data is shared with 3rd parties and on what terms that sharing happens. Think about this specification as a 'data contract' and an addendum to the privacy policy of the service

2: Companies must make APIs available to allow people to download their information at any point of time and this information will comply with the technical specification of #1

3: Companies must support storing and retrieving this information for a person at any and all times in a data storage platform specified by that person. This data must always match the information stored in the internal systems of the company

4: Companies must allow persons to demand that all data about them is only stored in their data storage platform and that none of this data must be stored in the internal systems of the company

5: Companies must not store any data about any of the people that use their platform but must store and retrieve that data from the data storage platform specified by those people

The thinking is, once you have full control over your data and, through the specification, know what that data means, you have full control of managing your data and its usage.

For more info, https://stevenhessing.medium.com/ and https://github.com/StevenHessing/byoda

Love this as a pragmatic overview - thanks!

Am I naïve in thinking that this could be helped with transparency legislation. Proper transparency legislation?

Here in Europe we are prompted to say 'I'm fine with this' when informed that a site is going to involve me in this ecosystem. Or not visit *the content I want to see, already 10 seconds ago* 🙄

But I would like to see a report from an app/site that told me a month later (if I wanted to know) exactly what data was captured & everyone it was pushed out to.

I feel stupid even thinking this could be a thing. Yet, apart from scale, what's the blocker?